April 1 2020: No April Fool.

How I lost everything … and who that made me become.

By Jocelyn Brady

April 1, 1990: The day me and my dad became homeless. I was 7. He had just left my mother. The lava was coming. We had to evacuate.

We had moved in 1990 from Southern California to the Big Island of Hawaii to, as I once heard my dad say, “never have to wear a suit and tie again, never have to sit in rush hour traffic,” never have to live a life of insane, inane busyness. To escape the Rat Race.

And on April 1, 1990, we found ourselves chasing the most basic human needs of all: Food and shelter. Our house in Kalapana Gardens was consumed by lava. Burned down. Gobbled up. Buried beneath several feet of freshly erupted magma.

We didn’t know anyone.

There was nowhere to go.

But we got lucky.

We found a homeless shelter, and if I remember right, they made an exception for a grown man, my sole guardian, to stay where women and children took residence—most of them evading dangerous domestic situations. All of us fleeing, free falling, trying to find some solid footing.

My dad got us on welfare. After a few months, we found a house we could rent thanks to subsidies provided by the Department of Housing and Urban Development. We ate a lot of peanut butter and chicken and took walks to splurge on $1 Happy Meals at McDonalds. (Back when they still came with cool toys. Is that still a thing?)

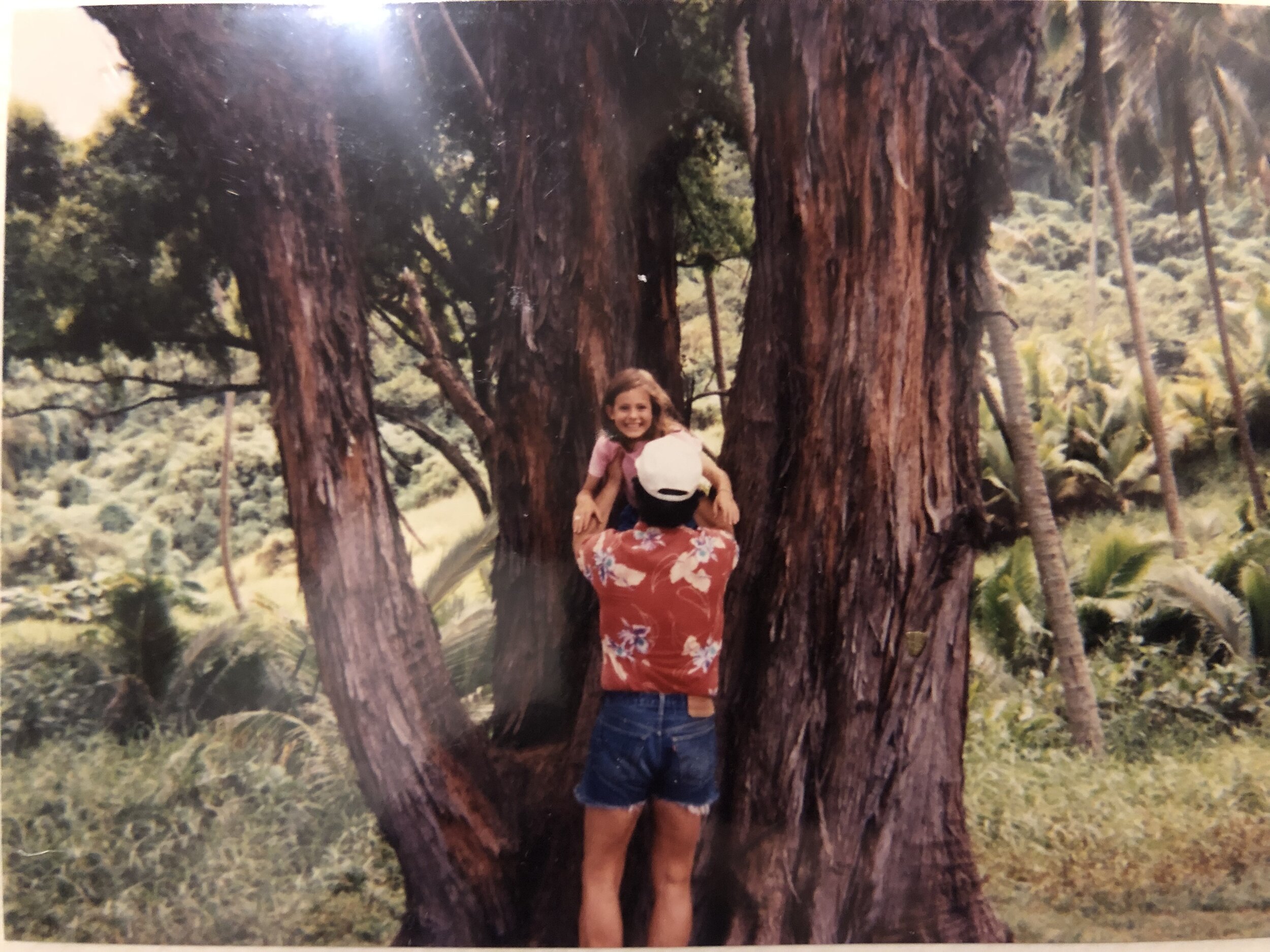

me and my dad circa 1991

We lived in a tropical jungle. We could hear the palms rustle and smell the jasmine bloom every night and we had all this land around us. I was free to explore.

I was lucky.

But I carried a deepening sense of shame that emerged in the company of others. I became mortified to show the Blue Card that proved I qualified for free lunch and free bus rides to school. Every time I had to take that Blue Card out of my bag or my pocket, I tried to make the act as swift and unnoticed as possible. “SHOW YOUR CARD!” a driver or cashier might holler impatiently if I tried to eke by unnoticed... And I’d feel the attention, all eyes searing as intensely as the scarlet blood rushing to my face.

Sometimes I would save up all this change I’d found or collected from somewhere, for weeks or months, just so I could stand in line and pay like the “normal” kids and not feel like looking over my shoulder, dodging the Blue Card stares and whispers and sneers from the kids richer than me. Kids who didn’t know better. Kids who’d never known what it’s like to have nothing, to have everything snatched away by forces beyond their control, to have to start over on ground zero.

A funny, strange, awful thing happened when I paid for lunch and bus fares with that saved up change. It’s like being upgraded to first class for the first time. You suddenly feel, ugh, proud. As if you did something worthwhile to achieve this new status. As if it wasn’t just money or luck or repetition that bumped you up. And sure, I suppose I worked for that “upgrade.” But at what cost? What else could that spare change have gotten me that I needed more than some illusion or escape?

Standing in line with change in my pocket, relieved from the anguish of displaying my Poverty Card, I fell into this trap of thinking. I felt a rising guise of superiority. As if my Class Upgrade made me better. Worthier. I’d watch kids busting out their Blue Cards and feel a stab of pain and guilt and shame as I thought about how I didn’t want to be one of “Them.” If anyone made fun of these kids, I didn’t stick up for them. I averted my eyes. I pretended not to see.

The real shame comes from seeing who you are in situations like these—and realizing you’re not as great as you want to believe. The cost of trying to fit in, of pretending, of hiding behind money or possessions or beliefs, is often the integrity of your character. It would take me years to grow out of my shame, to untether my sense of worth from how others see me and my "net worth."

I regret how long I played the fool, and the damage it must have done.

Poverty

is

insidious.

It messes with your brain. Literally.

In a 2015 study published in JAMA Pediatrics, researchers found “that low-income children had irregular brain development and lower standardized test scores, with as much as an estimated 20 percent gap in achievement explained by developmental lags in the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain.”

Photo by akesak/iStock / Getty Images

But again, I was lucky. I got a lot of love at home and my dad, an educator (among at least two dozen other professions and labels), instilled in me a deep and lifelong love of learning. I read at a college level in third grade. I qualified for the state’s “Math Bowl” competition (where numbers kids race to solve math problems in small teams). Doing well in school was never a problem for me. Until it came time to speak in front of people.

I once took an assignment Fail in fifth grade for telling the teacher I couldn’t read my autobiography out loud in the front of the room. I worked like hell to make that story great. But when it came time to talk in front of my peers, I felt like I was standing up there as a giant Blue Card. I didn’t want anyone to see, to laugh at me, judge me, think of me as inferior. The teacher didn’t care about my fears. And to be fair, I didn’t play by the rules.

I sat it out, buried my face in my folded arms, tears streaming into the crevices of my elbows. I got a C in that class. My first C. I cried about that, too. A lot. Good grades had become a part of my self worth. And so unworthiness pervaded.

Still, in the grand scheme of things, like I said: I was lucky. I’d eventually graduate high school and get a graduate degree and start a business and buy a house and start a retirement account and checkmark the hallmarks of the American Dream. I’d eventually move out of poverty. But the survival instinct always remained. The thought, the belief, that everything could always be taken.

Security, especially in America, is an illusion.

Photo by MattGush/iStock / Getty Images

Photo by kevinruss/iStock / Getty Images

I think today of all the people who are facing dire circumstances.

Afraid of whether they’ll get another paycheck, another meal on the table, another day of water and power. Another day of knowing where the hell they can live and take care of their families.

America is in turmoil. The population of people struggling financially is hard to quantify. But one thing is clear in the time of Covid-19: that number is growing. Exponentially.

The United States Federal Government estimates that we have 550,000 homeless people on any given night. And 1.4 million who live in a shelter any given year. But I never understood how they could count everyone. It’s easy to discount what you can’t, or refuse, to see.

The numbers we can see have a troubling story to tell. In December of 2019, a Gallup Poll showed that a quarter of Americans say they or a family member have delayed medical treatment due to the costs.

At least 31 million Americans rely on safety net clinics for care they can’t get—homelessness, poverty and illiteracy prevent access to health insurance. Those safety nets too, are running out of funding. Those without are finding fewer options to turn to.

Over 20% of all children living in America already lived in poverty before this disease struck. Nearly half had already been living in low-income households. Thirty million kids. What kind of world are we creating for them? What will happen to their brains—sponges thirsty for knowledge and care and love—as their situations and outlooks look bleaker and bleaker by the day?

In the wake of corona, businesses are shuttering and laying off workers en masse. More than three million people applied for unemployment in this last week alone—more than at any time in history. Forty million Americans might lose their job by April.

As layoffs mount and gig workers can’t find steady work, the numbers will surely grow. A system where people secure health care through employment is experiencing the biggest job loss we’ve ever seen. Access to healthcare is shrinking. How many bodies can we count?

These aren’t the numbers and realities we hear and see most from our leaders. We are bombarded by news of falling stocks and fears of recession. The loudest voices with the deepest pockets are lobbying for cash infusions to stabilize the economy, virtue signaling salvation. Two trillion dollars are generated out of seeming thing air. Some of us will get a check for $1,200. The average rent in America is $1,405. While countless Americans decide whether to buy food or medicine or pay for rent, the top 1% receive yet another tax break amidst it all.

This is America today. A country of nearly 330 million humans. At a point in time where it’s painfully clear just how long we’ve been collectively turning a blind eye to the disease we’ve been living with for far too long: A class system under the guise of Capitalism. A society so focused on profits it fails to see the costs of losing its character and integrity.

April 1, 2020: What we thought we could rely on is disappearing right in front of us. It’s time to evacuate a faulty foundation. It’s time to look around. At the kids and parents and workers and artists and our elders. At the human beings who make us who we are and are right now overridden by fear and losing access—if they ever had it—to the basic essentials of survival.

We need to rebuild with a fresh perspective. Stop playing the fool. Because what’s at stake right now is the most essential thing of all: our humanity.